ProPublica’s Haspel Correction Highlights Bugs in Journalism’s Code

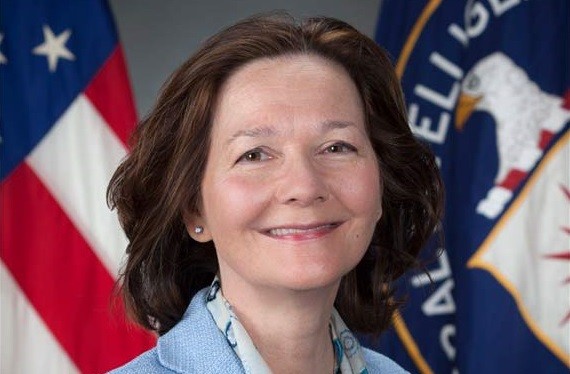

ProPublica’s tag line is “Journalism in the Public’s Interest.” Unfortunately, its recent coverage and subsequent correction around CIA director nominee Gina Haspel’s responsibilities for waterboarding in Thailand is one more self-inflicted wound that undermines the credibility of journalism. This is definitely not in the public’s interest.

Let’s be clear. ProPublica is an outstanding media organization and does great work. It breaks important story after important story. And, it deserves credit for acknowledging major factual errors that shaped the direction of their article which focused on Haspel’s responsibility for and response to the waterboarding of Abu Zubaydah.

Their very visible correction retracted the key elements of the story and highlighted the process that led to the inaccuracies. Mea Culpa.

That should be it, right? Heroic reporters uncovering the truth are humans. They occasionally get it wrong. And when they do, they confess, say three Hail Mary’s, and we can move on.

However, that’s not how journalism or journalists position the profession.

When you claim to be “the” purveyor of truth, as in “The Truth is More Important Than Ever” – The New York Times’ tag line – the response to mistakes is a “this does not compute” meltdown. In ProPublica’s case, in the correction the baby was thrown out with the bath water.

Not that I am arguing that mistakes are OK.

When reporters are wrong in the hyper-political world we live in, inaccuracies are weaponized. They are used with a broad, indiscriminate brush that labels even the truth as questionable.

With each failure we lose the anchors that underpin trust in journalism. When we don’t know truth from fiction, conspiracy theories and the potential manipulation of audiences becomes easier.

In a perfect world we would not see reporting errors. Nonetheless, we need to recognize that these “bugs” are the result of a human system. Even with significant checks and balances, it is fallible.

When a story is as wrong in its reported facts as that of the Haspel story, it’s natural for the entire thesis to be dismissed. That’s a problem for a story as important as this one.

ProPublica’s headline for its correction reads: “Correction: Trump’s Pick to Head CIA Did Not Oversee Waterboarding of Abu Zubaydah.” What’s lost is the most important takeaway: According to media reports, Haspel was responsible for the CIA operation in Thailand that used waterboarding on at least one detainee and may have ordered the destruction of video tape evidence of this activity. Her upcoming confirmation hearings are expected to, in part, focus on and clarify her role.

When inaccuracies are used as bludgeons against media organizations it is, perhaps, no surprise for this emphasis on what was wrong, not what was right. Especially when there may be legal consequences.

But, there’s an additional dimension at play here – journalism’s own rules.

Being wrong conflicts with its professional code.

When you position yourself as “holier than thou,” the not uncommon response is something like, “I have sinned. I will now publicly flay myself.”

Frankly, this is in no one’s interest.

It is reasonable to argue there’s a conflict with the need for journalists to get the facts right and then to say that journalism should not self-immolate when it gets them wrong.

As with any professional ideology, it’s the ideas and rules of the profession that help it maintain its standards. When they are breached there should be consequences as a self-policing mechanism.

But, there’s a bigger goal at stake. For an industry focused on the public interest it is important to ensure that what is right about a story is not lost.

It is essential that journalists have a rigorous process to get its fact right, but also to admit that they are not gods. They are mortals doing the best they can to seek and share the truth – at best, an elusive concept to which they (like all of us) bring their own perspective and biases.

The key is to recognize that the “bug” in the “journalism code” is in fact a feature (unless of course this is done deceitfully). It is to be human in a human profession.

If we recognize this, and journalism is a little humbler in its ambitions for being the arbiter of the truth, it is less likely be “hoisted by its own petard” when it fails. And, to issue more balanced responses when it doesn’t get things right.

This is in the public’s interest.

Simon Erskine Locke, Founder & CEO of CommunicationsMatchTM

Locke writes extensively on issues related to communications, PR, media, and behaviors.

Prior to founding CommunicationsMatch, he held senior corporate communications roles at Prudential Financial, Morgan Stanley and Deutsche Bank and founded communications consultancies.

Read other crises communication articles on our Insights Blog: “Bloomberg & Social Media, PR's Social Media Crisis, Social Journalism & Crisis Communications, PR is Not Dead (Video)”, “Honesty in Communications: Not Only The Right Thing, But The Smart Thing”, “Crisis Communications Measurement: Metrics That Matter”, and more.